L A N D S C A P E S O F M A T T E R

The human mind may not have evolved to be able to comprehend deep time. It may only be able to measure it.”

-John McPhee, Annals of the Former World

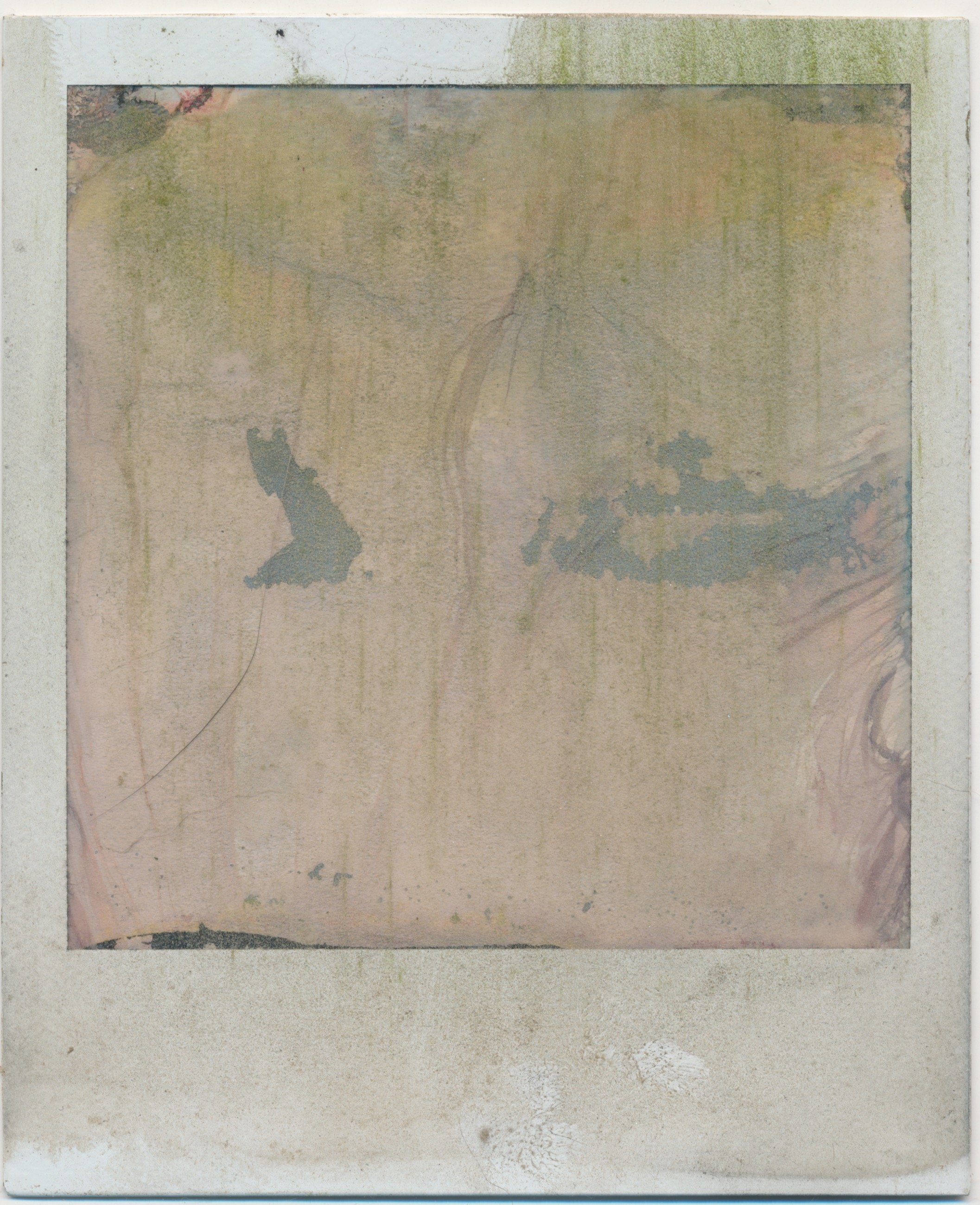

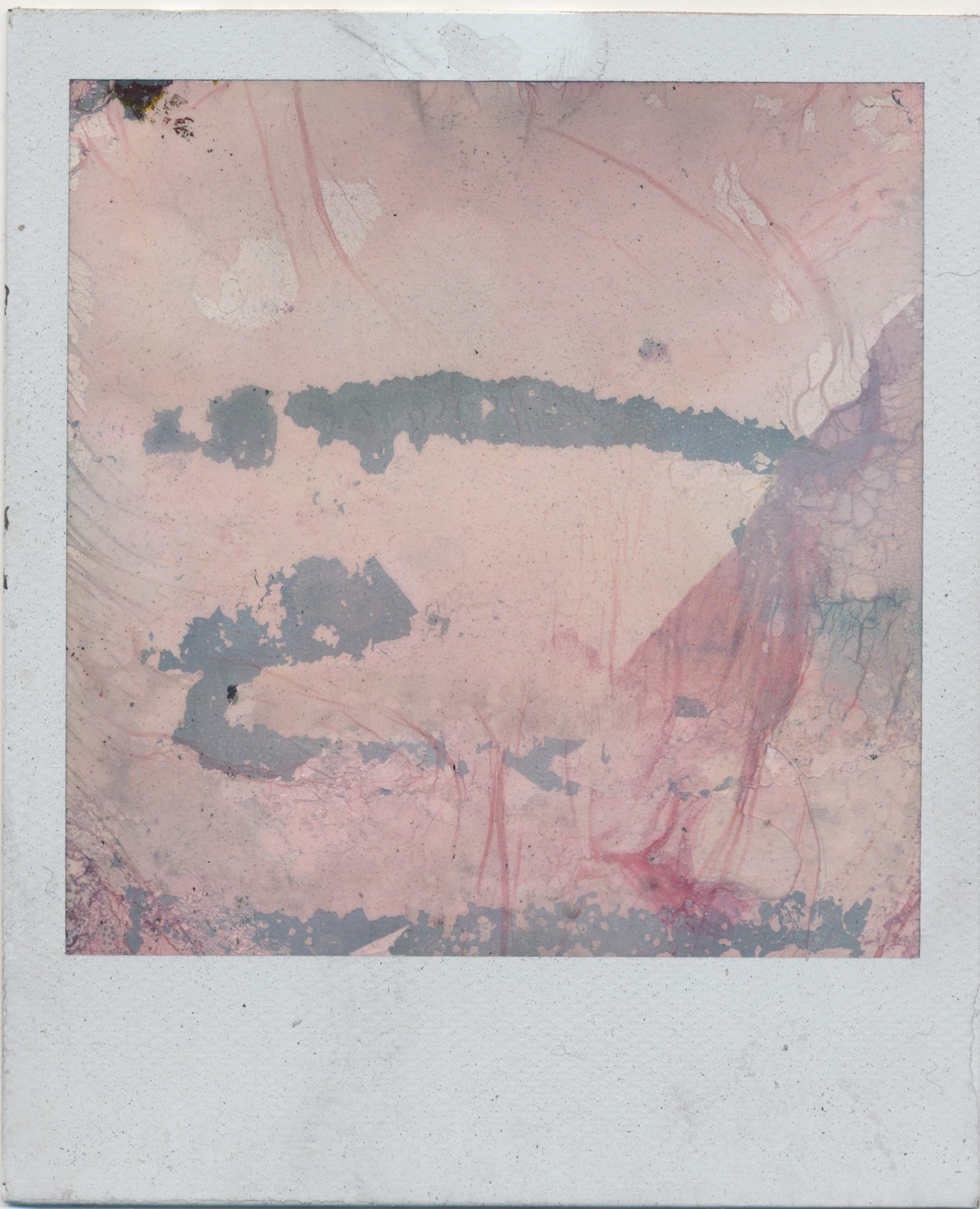

Landscapes of Matter is a multimedia, time-based exploration documenting the geologic and anthropogenic violence impacting the landscape between New Orleans and Venice, Louisiana, where the mouth of the Mississippi flows into the Gulf of Mexico. Using instant film technology to capture the temporality of the environments and their ongoing shifts under the arcs of slavery, settler colonialism, racial capitalism, and patriarchal violence, Landscapes of Matter both exposes and archives the visual messages of ecological and racialized violence.

Through the use of instant film photography, which has seemingly withstood the tests of its time, proving its longevity and worth of existence in a time of disposability and desire for faster, better, more controlled technology, I take pictures of natural environments between the 100 mile stretch below New Orleans to the Gulf of Mexico and then immerse the images in dirt, water, plant, matter, sunlight, and related natural elements, allowing the environment itself to continue the film development process.

VENICE, LA

Venice, Louisiana is home to “The End of the World”, the southeastern most tip of land in Plaquemines Parish that can be accessed by car before the mouth of the Mississippi River spills into the Gulf of Mexico. A ways up from this sign is a gravel road that extends to a point beyond the welcome sign pictured below, where an industrial plant stands alone — the trees, bear sick fruit, there is less natural sound (birds, insects, animals), and the water is toxic. The following images were captured in November 2021, and submerged in gathered matter from the waters within a 0.5 mile radius of the welcome sign.

This process is time based — all Polaroids were submerged in water for one full moon cycle, or 28 days.

The earth will survive us. I want to bear witness to the messages that the earth is leaving behind through instant photography, as it leaves us behind in the labyrinth that is deep time.

According to John McPhee in his survey of geology, Annals of the Former World, humans exist in a comfort bubble of five generations — “two back; two forward” — a place from which deep time can appear as the equivalent of ancient history. In our current world of socially-impulsed shared seconds, minutes, and hours, the images we see conjure pseudo-realities where the spatiality of our social geography is speculative at best, and with conspicuous consumption. The structures of our environment have become increasingly stratified by the temporality of the digital world.

Those who are direct beneficiaries of ecological and racialized violence have a deistic grasp on existence, and behave as if they are entitled to control the natural and built environment. The earth itself is responding to this continuous violence, to the taking away, by withholding — but we are not listening. We discard the visible messaging as “constructed by humans”, or as insufficient evidence, or more commonly, out of sight, out of mind. This anthropogenic degradation is also the desiccation of human existence — disproportionately impacting people of color and poor communities.

This project is captured on a Polaroid SX-70 camera (produced 1972), Polaroid Sun 660 (1981), Polaroid Supercolor 670 AF(1990), Polaroid Now+ (2021) and, when possible, a Polaroid Spectra (2000) camera. Polaroid’s instant film is considered to be integral in that it incorporates timing and receiving layers to automatically develop and fix the photo without any intervention from the photographer. These five cameras will serve as metaphors for five generations, as they represent different advancements in technology and image-making, as well as the consequences of being defunct, discarded, or disposable.

I am curious to see what a defunct, or expired, image produces in environments that are also viewed as defunct, such as closed industrial plants, or expiring, such as the eroded lands of southeast Louisiana, as well as those landscapes and waterways that are deemed as “functioning” and are still actively inhabited and utilized. In forming a micro-historical, genealogical, geological photographic collection, I am investigating the affects of human and environmental temporality with nature itself operating as a direct influence, or co-creator, of the images.